As a kind of anthropologist, US-Swiss artist Christian Marclay epitomises the participant observer, charting from within the material cultures, interactions and commodity exchanges of two hugely important 'empires', image and sound. Their intermingling generates much of our popular culture but they have arguably yet to come to a full understanding of each other. Marclay has been exploiting this divide and charting its borders for over thirty years as an experimental musician and artist working with the legacies of performance art, Fluxus and punk since a move to New York in the late seventies.

Replay: Christian Marclay, originally curated by Emma Lavigne for the Musée de la Musique in Paris, unfortunately tells only half that story. Marclay's many assemblages and sculptures, including his well-known record cover collages and the floor of CDs to be scored by people's feet are missing from the exhibition. This will frustrate those looking for a 'proper' retrospective, and is doubly unfortunate because Marclay's insight has always hinged on the commodified materiality of musical and visual culture.

Nevertheless, in the videos that wholly comprise the show, Marclay's shifting emphases are clear. A few early performance videos chronicle the urgency of punk and its DIY dictates regarding the virtues of ineptitude. Marclay's independent, almost-too-good-to-be-true appropriation of turntables and LPs (it still defies belief that Marclay, in NYC in 1978, could be unaware of the pioneering hip hop experiments of DJ Kool Herc or Grandmaster Flash) as anti-virtuosic performance strategies are minimally outlined.

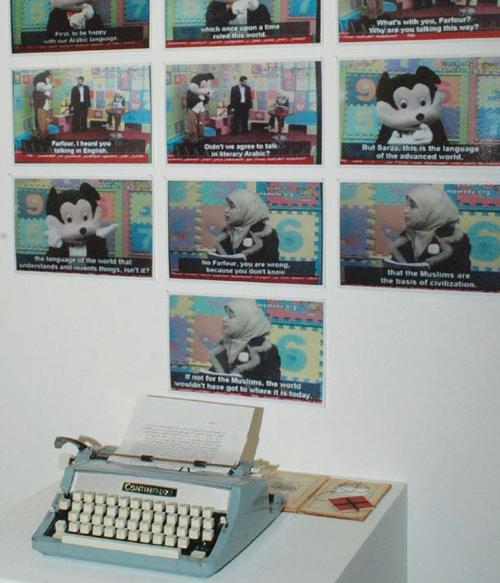

A discernible insistence on his own virtuosity leads logically enough to the main emphasis of Replay Marclay, the artist's later experiments with film, that allow Marclay to remix visual representations along with the continuum of music, sound and noise. Marclay's film re-edits are primitive but pleasurable deconstructions. Telephones (1995) for example, one of the earlier video works included is nothing more than a montage of people using telephones, drawn from a wide variety of films. These clips are put together in a way that makes it seem that there is one comprehensible conversation taking place.

Steve Martin did the same thing twenty-five years ago in Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid by mixing live-action with 'found' footage to make it look like he was on the phone to Humphrey Bogart. Marclay however pushes these Gestalt games much further, while maintaining the humorous strategies that Martin's comedy classic deployed. Marclay shows us the workings of the cinematic apparatus by stretching the grammatical glue of shot/reverse/shot to its limits (the telephone changes colour and shape from shot to shot but it's still ringing so we patiently wait for someone to answer it). This is unquestionably pleasurable, like the sensation of perceptual puzzles where we teeter between two mutually-exclusive images: the duck/rabbit effect.

Marclay begs us to show off our filmic knowledge, even while using the original clips 'formally' so that this knowledge is not strictly necessary. Recognising, say, James Stewart in Vertigo offers another layer of enjoyment, unleashing parallel or even conflicting narratives and associations as we consider the Hitchcock film alongside the Marclay video.

Part of the fun in these genre pieces, including the musical compilation Video Quartet (2002) and the percussive gunfire spectacle Crossfire (2007), is in Marclay's manipulation of filmic syntax, the tropes and clichés that characterise answering the phone, slow and deliberate or crazed lunge, or the sexualised grammar of firing a gun, unsheathing it, letting off a burst, stopping to breathlessly reload, the final climactic shoot-out.

As a border-crossing participant, an observer and bricoleur native to neither the zone of music or sound, Marclay is open to charges of only superficially understanding the genres he nominally reinvigorates. In this view he is neither a good musical composer nor an attentive film historian. Marclay's best works, like Crossfire or Video Quartet, might not make interesting headphone music, and they are not video essays in the style of an artist like Chris Marker, but really these criticisms miss the point. Marclay's practice is best understood as spectacle, a total synthesis of image and sound. Spectacular, like the popular culture it's pieced together from, but when played back it can help us distinguish signal from noise amidst the cultural din.