It was unseasonably warm in Yogyakarta when I visited in November 2023. Temperatures soar to an average of 38 degrees Celsius each day. There was no rain for almost three months causing crops to dry. The heat was inescapable, a constant reminder of what it means to make, produce, curate and experience art in the world today. This extreme climate was the backdrop for Biennale Jogja 17, Titen: Embodied Knowledges, Shifting Grounds, which featured more than 60 artists and collectives from Indonesia, South Asia and Eastern Europe. For this edition, works were presented outside of museum and gallery spaces, across seventeen locations and villages and often in semi-outdoor settings such as community centres, warehouses, farms and community gardens. This approach intended to bring the exhibition closer to the local community and to reemphasise local Indigenous knowledge that grounds the Biennale’s curatorial endeavour.

Rising temperatures are not unique to Indonesia, but equatorial regions including Southeast Asia, Africa and South America share similar climate change impacts and ways of living. The Equator forms the foundation of Biennale Jogja’s Equator series which enquired into the arts of equatorial regions, strongly anchored to the politics of the Global South. Each series are delivered every two years over ten years (2011–21); Biennale Jogja 17 2023 marks the second round of the Equator series (2023–27) which seeks to reassess power-knowledge relations in the contemporary world through ecological, social, political and historical issues, and place an emphasis on shared local and trans-local knowledge systems that emerged in the Global South and South-to-South relations.

As the title suggests Titen: Embodied Knowledges, Shifting Grounds, highlights the importance of revisiting and resituating indigenous knowledge systems within contemporary society and everyday living. In Javanese, titen or niteni (ilmu niten) is interpreted as the ability or sensitivity to read signs from nature based on a pattern of repeated observations. In an interview with Biennale Jogja Director Alia Swastika, she shared that:

Titen articulates the urgency for curators to care for local indigenous knowledges and at the same time try to find and imagine renewed relevance and importance of these local knowledges to everyday life at present.[1]

A striking example of titen is Indonesian artist Aji Ardoyono’s kinetic installation Evolusi Kinetika (2023), who observed the disappearance of dragonflies in his hometown of Bandung in West Java. Dragonflies are bioindicators of the cleanliness of water and their disappearance indicates the rise of polluted waterways. Evolusi Kinetika is comprised of large kinetic dragonflies made from recycled materials. The constructed insects observe the relationship between nature and technology, offering a glimpse of a ‘constructed’ man-made future. Displayed in an open-air community centre where school group gatherings, dance, performances, and cultural events take place, the installation’s site emphasised the relevance of living organisms within the shared nature and human ecosystem.

A recurring thread across Biennale Jogja 17 is women’s roles in caring for nature and as keepers of local knowledge systems. The works of Indonesian women artists such as Fitri DK, Monica Hapsari, and Arum Dayu address the broad themes of activism, motherhood, collective care, farming and nurture. Each collaborated with local women’s groups and communities and presented multiple expressions of local knowledge through storytelling across installation (DK and Hapsari) and video (Dayu).

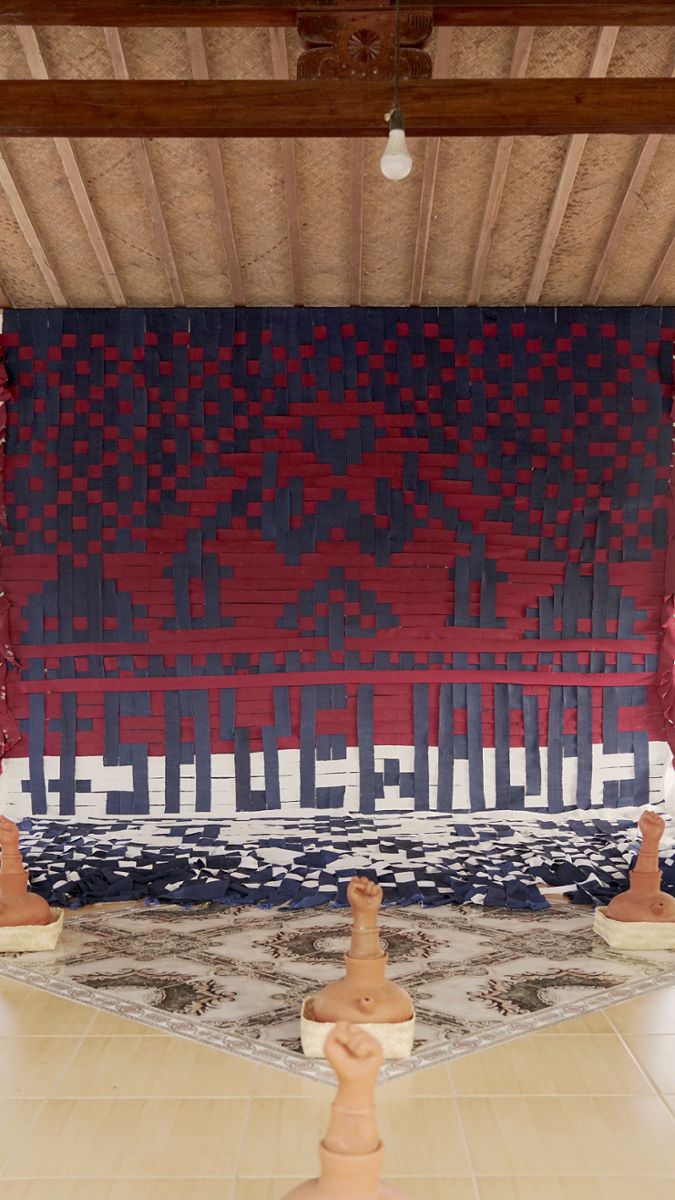

Fitri DK’s work Wadas Lestari (2023) centres on women’s resistance and collective action in Wadas village in Purworejo regency, Central Java, against the (igneous rock) andesite mining in the area. Women in Wadas play an important role in agrarian social relations using bamboo craft and weaving as forms of resistance to preserve and protect their land, environment and way of life. Bamboo grows abundantly in Wadas village and women have collectively woven besek (baskets) to secure and guard their land from developers. In addition, women would use stagen (traditional Javanese corsets) to wrap and cover trees so that they are not chopped down for construction of mines. Fitri DK’s installation draws on this local practice, using woven stagen cloth, batik, bamboo baskets and pottery that encapsulate the spirit, activism and strength of women in Wadas village, acknowledging their efforts to preserve their land for generations to come. While the theory is not explicitly evoked by the artists, this eco-feminist element of the Biennale offers a stimulating curatorial angle, and is a powerful reminder of women’s contributions to environmental management in the contemporary world. Swastika described the eco‑feminist direction of Biennale Jogja 17 as evolving organically, led by artists already active with women groups in various communities:

When we speak about the environment, local knowledges and everyday practices it became evident that women play a big role in the daily life in desa (rural areas/villages). We don’t see eco-feminism as a theme, but it becomes a tactic that unfolds in the working process of the curators and artists in Biennale Jogja.[2]

As for artists and cultural producers worldwide sensitive to the carbon impact of their practices, the artists and curators of Biennale Jogja 17 made a conscious effort to strategically use materials that are readily available, organic and can be recycled or reused by locals after the Biennale. One of the more ecologically animated works was Yogyakarta-based art collective TacTic Plastic’s installation made entirely of plastic waste shaped into colourful arrangements of plants, flowers, crops and vegetation. Kayun Kalamangsa: Ngrumat Arep (2023) was a direct response to changing climate conditions and the decline of Pranata Mangsa, a local knowledge system based on a calendrical system used by farmers to start seasonal plantings and associated agricultural activities. Materially, the work illustrates the contrast between the organic and the processed, a stark reminder of the lasting permanence of plastic within the environment.

According to Statista’s 2022 data, there are 400.3 million tons of plastic produced in the world each year and only a small share is recycled.[3] Indonesia generates approximately 7.8 million tons of waste annually and 62% of this is mismanaged—either uncollected or disposed in overflowing landfills, open sites and into the ocean.[4] Indonesia’s plastic waste issue is largely attributed to the import of rubbish from countries such as Australia, the USA, Europe, Japan and South Korea, especially following China’s import ban of foreign plastic waste in 2018. As such the plastic waste emergency in Indonesia is not only a national issue but a global one despite the severe consequences being faced by Indonesians, such as dealing with contaminated food chains and poor access to clean water.

TacTic Plastic collaborated with researchers and geographers to map out the spread of plastic waste specifically in Yogyakarta, finding that the majority of plastic waste was plastic bags often found near universities surrounded by mini markets and supermarkets. The work presents a glimpse of what a plastic world and environment could look like and the urgency to take action. More importantly, staging Kayun Kalamangsa: Ngrumat Arep as part of an international art exhibition such as the Biennale Jogja, demonstrates that we, as citizens of the world, are all complicit in the plastic waste crisis in Indonesia and together have a responsibility to care for and think wisely of our waste.

The Biennale’s emphasis on knowledge reframes the responsibility that comes of knowing. Art works are not to simply “tell” or “reflect” on these issues, but to invite audiences to think, question and imagine ways of knowing, and therefore living. So, what is our responsibility as bearers of local knowledges as they relate to our environment and livelihoods?

These questions remain unaddressed throughout the Biennale, and I would argue they are crucial in bringing forward eco-critical values in the contemporary art world. Apart from the Biennale’s curatorial framework and practical efforts to limit waste, there seems to be a lack of follow through with its ideals, which risks it becoming yet another Biennale in which themes and directives, or best intentions, dissipate, replaced within a few years by the next curatorial agenda.

If we question how a biennale could be eco-critical, it needs to be interdisciplinary and commit to ongoing dialogues, educating the public and preserving knowledge beyond the course of the exhibition. This is an issue that is not unique to Biennale Jogja but to all art world activities and events. Biennale Jogja’s focus on collaborating with farmers, heads of villages, scientists and activists, in addition to artists, creates the possibility for continued engagement with ongoing ecological issues and urgencies and thus offers a promising working/curatorial model. Notably, ruangrupa’s efforts at documenta fifteen (2022) attempted similar work. However, the commitment to ensure such collaborations last beyond the duration of the Biennale is hard to measure. It requires not only engagements with art and exhibition‑making process, but also community‑building and ongoing knowledge sharing, as well as environmental commitments at government levels. On a more practical point, and one that applies to all global art biennials and triennials, is the lack of transparency regarding where artworks end up—if not acquired by collectors or institutions—and whether materials were indeed re-used or re‑purposed. If anything, Biennale Jogja 17 reveals the struggles of committing to ecologically motivated art and exhibition-making practice, even with the best intent to ‘shift the ground’.

Footnotes

- ^ Alia Swastika, unpublished interview with Bianca Winataputri, 7 February 2024

- ^ Ibid

- ^ Madhumitha Jaganmohan, “Annual production of plastics worldwide from 1950 to 2022,” Statista, 30 January 2024

- ^ World Bank, Plastic Waste Discharges from Rivers and Coastlines in Indonesia, Marine Plastics Series, East Asia and Pacific Region (Washington DC: 2021).