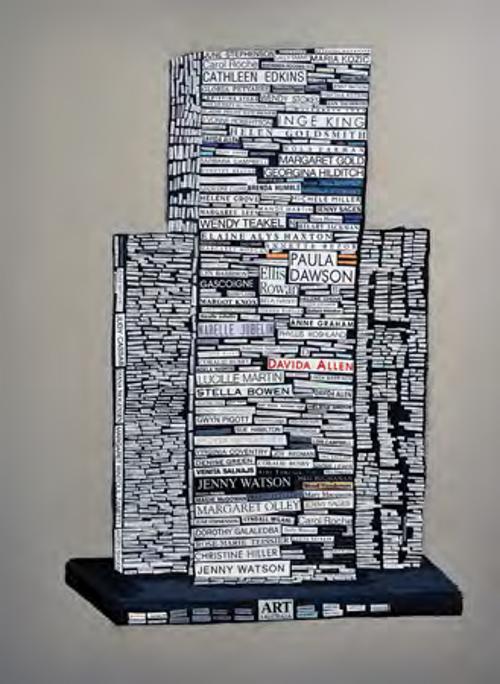

In her 99th year, the redoubtable Inge King (née Ingeborg Viktoria Neufeld) must surely be Australia's most senior and still practising artist. A career of such longevity, persistence and artistic vigour has been in want of a comprehensive survey from a major national institution for decades. The previous public exhibitions of any note were Form.Space.Experience (1990) curated by Judith Trimble at Deakin University Gallery (1990), and Inge King: Community and Public Sculpture (2000) at City of Manningham Gallery – each included under forty of King’s works. King’s influence, as a leading exponent in the development of non-figurative sculpture in Australia, remains considerable.

David Hurlston, the NGV’s Curator of Australian Painting, Sculpture and Decorative Arts to 1980, has shepherded this project through a six-year development. Inge King: Constellation traces the artist’s surviving sculptures from the mid-1940s to the present day, with the addition of several works on paper. Hurlston was a student of King’s husband, master printmaker and educator Grahame King (1915–2008), and has a long familiarity with the couple’s work. The collaborative and supportive role Grahame played in his wife’s career, throughout nearly sixty years of marriage, is acknowledged within the exhibition content.

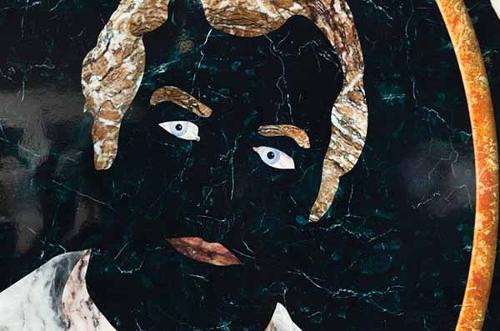

Inge was born in Berlin and studied at its Academy of Fine Arts from 1937, until the anti-Jewish stance of the National Socialists made her future in Germany untenable. In 1939, she fled to England, spending two terms at the Royal Academy before continuing her education at the Glasgow School of Art (1941–43). She joined a number of émigré artists at the Abbey Arts Centre, London in 1947, the same year she met the visiting Grahame. They married in 1950 and returned to Australia early the following year where they began to exhibit their respective works almost immediately.

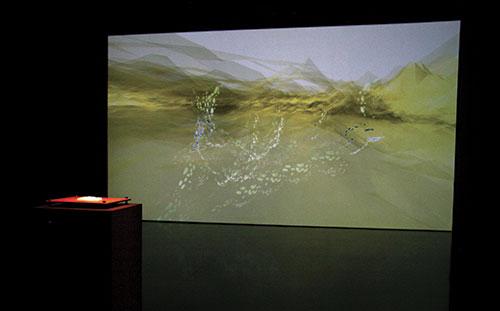

With the temporary exhibition galleries at NGV otherwise occupied, Constellation is split over three levels of thoroughfare and surrounding spaces, which unfortunately compromises its flow and overall coherence. The decision to place three works inside Café Crossbar on Level 3, Wall Sculpture (1963 & 1978) and the free-standing Rings Around the Moon (2011), is problematic. There is no signage to indicate their presence, and the context seems jarringly inconsistent with the formality expected from an exhibition of this standard. Navigation issues also impact other works. Sentinel, Maquette (1999) is positioned in an alcove of the stairwell between Level 2 and the ground floor. The red, blue and black work suits the space, but if you took the escalator or the lift you would probably miss it. Similarly, Awakening, Maquette I (1984–85) is placed on the escalator landing between the ground floor and Level 2. Listening stations, on Level 3 and the ground floor, provide some background to King’s career, highlighting key works and identifiable themes within her practice.

The exhibition encompasses the extremes of scale to be found in King’s output. One of its more fascinating aspects comes in the form of two cabinets of jewellery, predominantly made from sterling silver, and incorporating precious stones. King had earlier dabbled in metal-smithing at Glasgow, but financial imperatives led her to pursue the field anew in Melbourne, and she enrolled in courses at RMIT. The jewellery King produced met with great success, and formed a large part of her creative work until 1962. Rarely seen since, the 16 pieces assembled here – cuffs, earrings, pendants, brooches, rings, and a sun-ray shaped necklace – draw on multiple decorative traditions, but with a decidedly Celtic tinge.

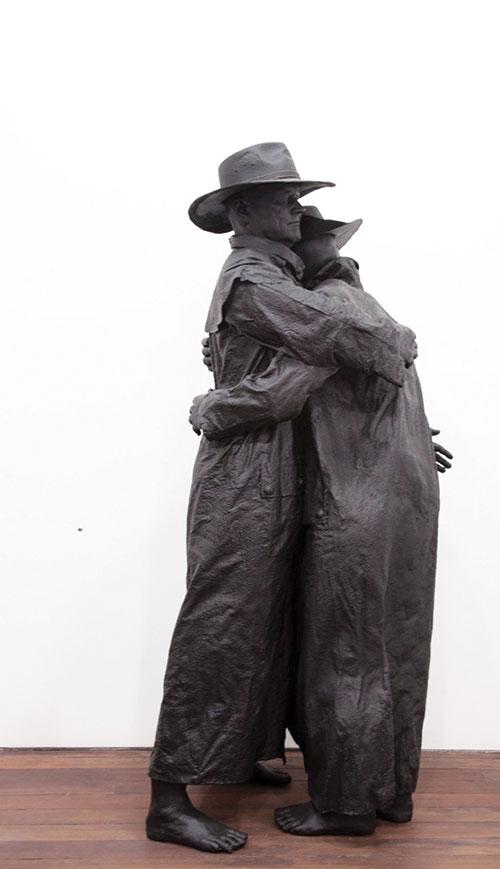

King’s eleven-piece exhibition Maquettes for Monumental Sculptures (1973) reaffirmed her desire to create substantial works for public spaces. King seldom sketches, with maquettes serving as her “working drawings”. The three for Black Sun (1974) show the developments in King’s process of determining the ideal size for any given sculpture. This is particularly insightful when viewing the small-scale version of one of King’s best known commissions, just down St Kilda Road on the lawn of the Victorian Arts Centre, Forward surge, maquette, Second version (1973–74).

The majority of the larger, more recent works are situated on the ground floor, presumably for logistical reasons. The vast glass panels and natural light in this setting enhance the shimmering stainless steel “celestial” sculptures that King commenced in 2004. Link III (2007–08) dominates the foyer, its interlinked u-shaped panels improbably balanced in a close arrangement of arcs. The gleaming Rings of Jupiter (3) (2006) and Celestial Rings I Second Version (2014) have an almost mesmerising, hypnotic quality, and represent King’s work at its most life-affirming and sublime.