.jpg)

Whether we acknowledge it or not, contemporary art and culture are subtly positioned within a dominant schema, primarily through the use of language. Language provides the frame through which visual culture is viewed, fixing its centre before overlaying it like a transparency against the much lauded ‘blueprint’ of the art historical canon. The closer those centres align, the greater ‘credibility’ our visual art and culture is afforded, somehow ‘legitimising’ an artwork and granting entrée into the rarefied world of institutional art museums. What privileges one artform over another? How is one cultural expression more ‘valid’ than another? What are the criterion that indicate ‘validity’, who set them and when?

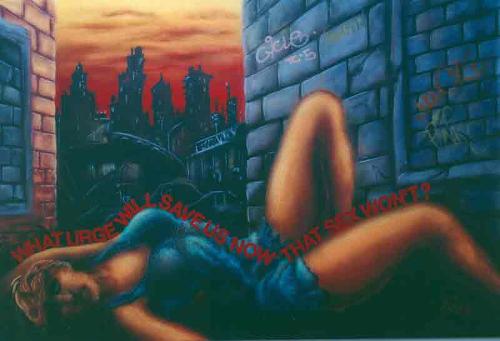

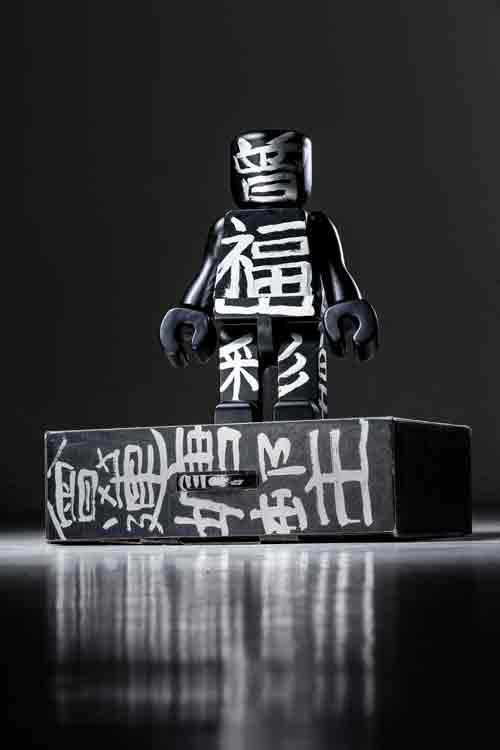

This issue of Artlink seeks to initiate discussion around graffiti as an artform, and examine how, why, and in what context it is considered legitimate. Can graffiti art exist in a gallery? How can an inherently transient and ephemeral artform be transported and conserved? How can it be collected and archived? Does it fundamentally change once it is severed from its situational context? These very questions are fraught in and of themselves – they assume an art historical framework as the central point of reference and, ironically, we hit a wall.

Indeed, artists with a graffiti art practice have not only transgressed the gallery space, but have already entered the art museum. The term ‘street art’, once defined by New York artist John Fekner as, “all art on the street that is not graffiti”, is now so mainstream that it describes a marketing aesthetic rather than an art practice. Meanwhile there are signs that traditional graff or ‘writer’ language is being abandoned, in many cases by the graffiti artists themselves, in favour of an art historical or art industry language as a means of repositioning graffiti as a legitimate artform. Crews call themselves collectives, writers call themselves artists, burners and pieces are called murals or works, and all city has been trademarked. Are we witnessing the gentrification (which invariably leads to loss) of a subcultural artform? Perhaps, paradoxically, graffiti art must fail as a traditionally ‘successful’ artform in order for its integrity to be preserved.

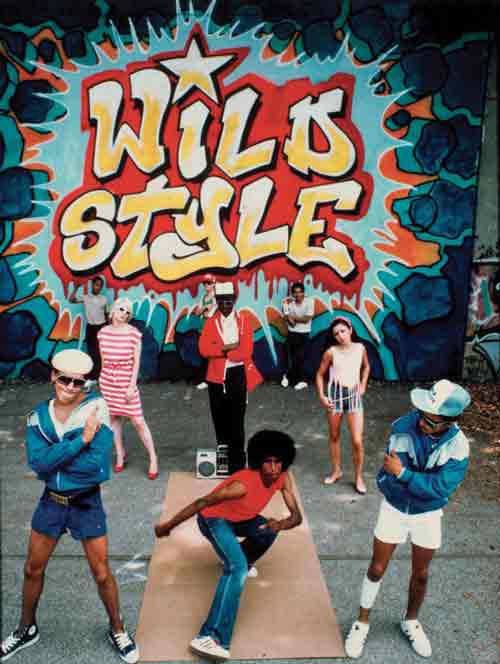

Rather than attempting to measure the legitimacy of graffiti art against an impossible, and inadequate, art historical framework, it is more interesting and constructive to examine the core of its intention and the alternative modes in which it has achieved great significance. Graffiti, (together with breaking, djing and emceeing, forming the base elements of hip hop culture) is a sub-cultural artform, and a legitimate creative cultural expression. It simultaneously interrogates the tension between notions of vandalism/destruction and the beautification/re-claiming of public space, whilst being a fundamentally political act that asserts presence by an often marginalised community with little or no voice in mainstream society. It reflects and celebrates the experience of local communities within a larger urban context by communicating neighbourhood identity and seeking to connect via a sense of place. With nearly 50 years of contemporary history, and a highly active worldwide practice, graffiti art has created a place for itself, spawned the street art movement and set the stage for the current trajectory from outsider culture toward the art historical centre – traditional definitions of ‘legitimacy’ aside.